Apprenticeships in Blacksmithing:

An institution of the past

The topic of apprenticeships comes up fairly often.

A search of our archives returned 32 responses when this was written and I have answered many more queries by e-mail in the past years.

I'm afraid the response is always the same and I suspect it is disappointing to those asking.

Historically an apprenticeship was bound by a legal contract and often regulated by law.

Apprenticeships were the only method to get an education in many trades.

The apprentice and his parents entered into the contract of apprenticeship with a Master Craftsman.

The Master agreed to house and instruct the apprentice in the craft as well as supply the apprentice with a kit of tools at the completion of the apprenticeship.

The apprentice was legaly "bound" as a laborer to the Master for a period of seven years and there was often an apprenticeship fee paid by the family.

This was not a free education. Besides the fee the apprentice worked long hours in the Master's shop every work day for the seven years.

A run-away apprentice was treated no different than a run-away slave and would be apprehended, jailed and returned to his Master.

A bound apprentice was the same as a bound servant except that the apprentice was supposed to get an education.

In the beginning the apprentice would have done menial tasks such as clean up duty.

In a blacksmith shop this meant sweeping, cleaning forges, putting away tools, cleaning rust off tools, hauling stock, fuel and water.

Coal or charcoal may have needed to be broken up and the ashes gleaned for good fuel or coke.

After some time tasks such as pulling the bellows and turning the great wheels that ran machines would be added to the apprentice's responsibilities.

It might have been a year or more before the apprentice was allowed to work metal.

Then it would be simple filing tasks, deburing and clean up.

Later as his filing skills improved the apprentice would be given jobs fitting hinge joints and such.

Meanwhile all the other menial duties would be kept up until there was a new apprentice to take over.

Eventually the apprentice would be given simple repetitive forging tasks like making nails or small chain.

As he developed he would be taught to swing a sledge hammer as a striker.

In most shops heavy forging was done by a team of strikers wielding sledge hammers.

This would often include the older apprentices and the Journeymen.

All part of the manual labor pool that would be replaced by machines in the 19th century.

After several years of working at menial tasks and watching the other smiths in the shop an apprentice would start to be taught various forging tasks.

In a large shop a Journeyman might have been instructed to teach the new apprentices under the watchful eye of the Master.

In a small shop the Master would do the teaching.

During this time the apprentice would be given materials to start making his own tools.

A few tools would be hand-me-downs and a few might be made by the master.

At the end of the apprenticeship the apprentice would have sufficient personal tools to be a Journeyman.

This would probably not include an anvil or other shop tools such as a forge.

A good master would have started paying a productive apprentice on a piece work basis so the apprentice may have had a small amount of money when it was time to become a Journeyman.

At the end of the apprenticeship the apprentice became a "Journeyman" and was usually provided with some sort of paperwork to indicate this status.

And as the term suggests the Journeyman was expected to travel to other places to find work in their trade and to further their education.

The Master presented the new Journeyman with his kit of tools (that had most likely been made by the apprentice) and he was sent off to seek his fortune.

In Europe this system was highly developed and controlled by the Guilds.

The Guilds had strict rules and awarded certificates of apprenticeship, Journeyman and Master.

After a period of time a Journeyman could apply for Master's papers by proving themselves to a board of Masters and submitting a "master piece".

Only a Master with papers was permitted to take on apprentices and to teach the trade.

In the Americas there was never an entrenched Guild system and the requirements for being a tradesman varied greatly or was not regulated at all.

There was such a lack of skilled crafts people in the early days that anyone with skills could set themselves up in business.

The old apprentice system had its advantages and disadvantages. At one time it filled a need.

A good Master would teach the apprentice everything from the math needed to perform his tasks to business methods.

However, occasionally there were abuses and Masters would use their apprentices as cheap labor and fail to teach what was required or they would mistreat the apprentice.

This happened often enough that most laws regulating apprenticeships had to do with these abuses.

On the other hand the apprentice may not have had a choice of trades and could find themselves bound to be a laborer in a trade they had no aptitude or interest.

The old apprentice system disappeared with slavery, indentured servitude and child labor.

The laws that freed slaves and indentured servants made it difficult or impossible to enforce an apprenticeship contract.

Today there are programs titled apprenticeships in some trades but they are generally not regulated or are specific to an industry, business or trade union.

They are no longer a work for education exchange but are generally a measure of experience upon which pay scales are based.

In most of these arrangements the "apprentice" has gotten their education from public schools and trade schools before going to work.

Today there is no true apprentice system.

Schools, both regular liberal education, higher education, colleges, universities, and trade schools have replaced the old apprentice system.

The labor exchange has been replaced by taxes supporting public education and fees paid for higher education and trade schools.

The medium of education and training is now almost exclusively cash.

Not only that but in the U.S. the tax system requires income taxes to be paid by the "employer" in some labor exchanges.

At a minimum they want taxes covering the value of room and board that may be provided to the "apprentice".

In Europe, notably Germany, there is still a system of certifying craftspeople and you can still get Journeyman and Masters papers there.

But this is becoming more along the line of our "industrial" apprenticeships.

Blacksmiths and Shops Today

Although blacksmiths in general do not make a great deal of money (you have to LOVE the trade), their shop time is

often worth more than $100/hour US.

Like most small business people, their day has many nonproductive hours required to operate the business and to sell their work.

Hours in the shop training someone are valuable shop hours that may have otherwise been spent producing work.

Expecting a skilled craftsperson to teach someone without proper compensation is presumptuous at best.

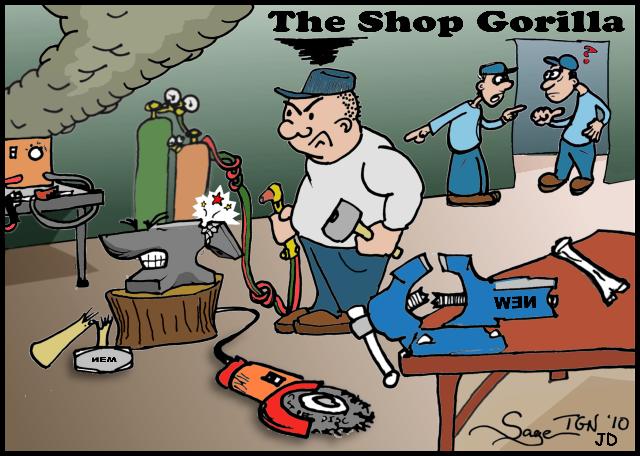

You hired him, YOU fire him!

Unskilled "apprentices" can be a huge problem in blacksmith shops.

A modern blacksmith shop is often the equivalent of a modern machine shop and welding shop with the addition of many rare and antique tools.

Most of this equipment has the built-in capability to be self destructive as well as lethal.

No matter what your current education level, if you do not UNDERSTAND machinery and shop safety you can be a huge danger to yourself, others AND to the very valuable machinery.

This problem is compounded by the fact that many very good blacksmiths are not nearly as well trained on this equipment as THEY should be.

They get by because they at least respect the machinery and know what it cost them.

The result of having an unskilled worker in the shop can be a swath of destruction that the smith may never recuperate from.

So the question IS.

What valuable skills are you bringing to the blacksmith shop?

Your previous years of education may not count for anything in a blacksmith shop.

Almost all shops have gas and electric welding equipment (MIG, TIG, Plasma).

Have you taken a full series of welding classes?

Although many smiths do not use arc welding in their work they will almost always have electric welding equipment for building fixtures and maintaining their shop.

Do you have any industrial safety training?

Architectural shops deal with drawings and specifications including the need to take accurate field measurements.

Do you understand measurement dimensioning and tolerancing sufficient to be trusted to take dimensions without someone double checking your work?

How well do you draw?

Read drawings? OR. . are you willing to spend a dozen hours or more doing menial boring work at minimum wage or less in exchange for an hour of your "masters" time?

In the more technical areas of smithing such as bladesmithing the top people have masters and doctorates in metallurgy and engineering PLUS years of self study in their field.

Have you looked into all the classes that are applicable to the specialty of your interest?

An amazing amount of blacksmithing is repetitive production work.

Look at a large piece of architectural work.

It may have hundreds of pickets scrolls or leaves that are all alike.

It may take someone days or weeks to just cut the stock to length.

After each piece is forged by a skilled smith each piece may need trimming, deburing and finishing.

Assembly often requires a LOT of brute force heavy labor.

Cleaning and painting is a HUGE part of the job.

Installation time can mean hauling a ton or so of tools and equipment on and off a job site every day for a week.

Every shop needs low cost laborers that don't dream of being artists or who want to play with the machinery.

This is a fact of life. So even if you get into a shop, they may not want to move you up. . .

The Good News

In North America and many other parts of the world most blacksmiths are very sharing and willing to give lessons.

There are also ABANA chapters in almost every state of the US as well as in Canada and New Zealand.

In Britain there is the British Artist Blacksmith Association and in Europe there are more organizations.

Your local organization is the best place to find out about lessons and where to get fuel and tools.

There are also more books on the subject of blacksmithing than ever before.

New books are constantly being published and old books are being reprinted.

AND there are the many web sites like anvilfire that have how-to, plans and information.

In North America there are now more blacksmithing schools than ever.

Most are operated seasonally and fill up quickly. Check the ABANA schools list and register early.

The ABANA Journeyman program: A Journeyman is much different than an apprentice.

A Journeyman may have skills far beyond what you expect for a "starter" position.

Check the recommended skill levels carefully on the ABANA web site.

A FEW shops will take on a "Journeyman" at minimum wage or so, depending on the needs of the shop and the skills brought by the, Journeyman.

It is a tough program to get into and get placed.

It is a voluntary program in which both sides need to work out the details. ABANA just sets the guidelines.

Documentation of all your blacksmithing skills may be needed.

Consider the difference between where you are now and the ABANA Journeyman level.

So how do you get to this level? See our Getting Started article. You take trade school welding and machine shop

classes (perhaps your college or University has some of these), then you go to the various blacksmithing schools .

You go to ABANA-Chapter meets and work on your own. Along the way you may meet someone willing to take you

on in their shop (probably without pay). It is not easy and requires a lot of self study.

Selected Q&A

I am a soon to graduate college student with a great interest in blacksmithing. I have dabbled for the last few years,

and would like to find a paid apprenticeship. I am a fast learner and a hard worker. Any ideas?

Scott - Sunday, 10/28/01 07:59:26 GMT

Paid Apprenticeship: Scott, That phrase is an oxymoron. Classic apprenticeships were an education and included

an apprentice "fee" on top of 7 years servitude in a binding contract.

That was the value of this highly desirable education.

I am sure your current education has cost tens of thousands of dollars ($100K +)?

So why don't you expect to have to pay for further education????

The classic apprenticeship is a thing of the past.

NOTE: Some businesses have what they call apprenticeships that start at minimum wage.

Usually these positions require that you have finished a general education plus specific courses covering the position.

This is often more of a trial position than an apprenticeship.

Other businesses will pay to put you through school while you work.

However, while working full time AND going to school you will only be paid a minimum wage.

Businesses that do this are generally desperate for trained employees and rather than training them in-house they have arranged for the local school system to do the job to their requirements.

This takes the burden off the business and takes advantage of a taxpayer supported school system.

These types of deals are made with large employers and would not apply to a small shop (unless it just happened to be in the same business).

Consider the offer I made last summer (2001). I needed someone to mow a 2 acre "lawn" (jungle actually), sweep shop,

clean and de-rust old machinery, dig ditches, do a little construction type work. Lots of menial tasks. In exchange, I

offered a place to stay (primitive) and meals. Access to my library and shop (within limits) and a couple hours of my

time a week in actual blacksmithing instruction (on top of the instruction necessary for the other jobs). My time was

based on a ratio of 12 or 14 to one. There were also some other perks. Trips to a private museum and other

blacksmith shops, local ABANA-Chapter meets and historic sites. The "apprentice" would have also gone home with

tools and equipment made as apprentice projects. Punches, tongs, swages, forge. . .

This is what I could afford in a apprentice deal.

The apprentice got an education in many areas other than just forging.

Much of the value to the apprentice depended on how his or her time was applied.

It would take a year to read my library of smithing and metal working references much less study them all.

Forge time was open ended with fuel and materials provided.

It was a worthwhile opportunity that had costs and benefits to both parties.

And, it is probably similar to what you will find in "apprenticeship" offers from others, until you reach that Journeyman level.

This offer is still open to the right person. Write to me.

Position filled for 2003-2004

Position no longer available. 2005 -

- guru Sunday, 10/28/01

Hi there.

I am very interested in becoming a blacksmith but have had very little luck in finding a local teacher. Could you

please let me know whereabouts I would locate someone in SOUTH AFRICA or where else I would be able to study

from. I am desperate! It is truly something I want very much to do.

Many thanks, and I look forward to hearing from you soon.

Carla - Friday, 11/16/01

South Africa: Carla, we have several regulars from South Africa that visit anvilfire but it has been a while since any

have posted. Those that I can think of are knife smiths. But there are many others that read our forums and do not

post questions or comments.

Post your message on our V-Hammer-In.

This page (the guru's den) is archived weekly but the Hammer-In is archived monthly so your message will be seen for a longer time.

Re-post your message if necessary.

Someone local to you may see the message and help you find the teacher you are looking for.

- guru - Friday, 11/16/01

References and Links

Copyright

© 2002 - 2011 Jock Dempsey, www.anvilfire.com

|

Apprenticeships in Blacksmithing:

An institution of the past

The topic of apprenticeships comes up fairly often. A search of our archives returned 32 responses when this was written and I have answered many more queries by e-mail in the past years. I'm afraid the response is always the same and I suspect it is disappointing to those asking.

Historically an apprenticeship was bound by a legal contract and often regulated by law. Apprenticeships were the only method to get an education in many trades. The apprentice and his parents entered into the contract of apprenticeship with a Master Craftsman. The Master agreed to house and instruct the apprentice in the craft as well as supply the apprentice with a kit of tools at the completion of the apprenticeship. The apprentice was legaly "bound" as a laborer to the Master for a period of seven years and there was often an apprenticeship fee paid by the family. This was not a free education. Besides the fee the apprentice worked long hours in the Master's shop every work day for the seven years. A run-away apprentice was treated no different than a run-away slave and would be apprehended, jailed and returned to his Master. A bound apprentice was the same as a bound servant except that the apprentice was supposed to get an education.

In the beginning the apprentice would have done menial tasks such as clean up duty. In a blacksmith shop this meant sweeping, cleaning forges, putting away tools, cleaning rust off tools, hauling stock, fuel and water. Coal or charcoal may have needed to be broken up and the ashes gleaned for good fuel or coke. After some time tasks such as pulling the bellows and turning the great wheels that ran machines would be added to the apprentice's responsibilities. It might have been a year or more before the apprentice was allowed to work metal. Then it would be simple filing tasks, deburing and clean up. Later as his filing skills improved the apprentice would be given jobs fitting hinge joints and such. Meanwhile all the other menial duties would be kept up until there was a new apprentice to take over. Eventually the apprentice would be given simple repetitive forging tasks like making nails or small chain. As he developed he would be taught to swing a sledge hammer as a striker. In most shops heavy forging was done by a team of strikers wielding sledge hammers. This would often include the older apprentices and the Journeymen. All part of the manual labor pool that would be replaced by machines in the 19th century.

After several years of working at menial tasks and watching the other smiths in the shop an apprentice would start to be taught various forging tasks. In a large shop a Journeyman might have been instructed to teach the new apprentices under the watchful eye of the Master. In a small shop the Master would do the teaching. During this time the apprentice would be given materials to start making his own tools. A few tools would be hand-me-downs and a few might be made by the master. At the end of the apprenticeship the apprentice would have sufficient personal tools to be a Journeyman. This would probably not include an anvil or other shop tools such as a forge. A good master would have started paying a productive apprentice on a piece work basis so the apprentice may have had a small amount of money when it was time to become a Journeyman.

At the end of the apprenticeship the apprentice became a "Journeyman" and was usually provided with some sort of paperwork to indicate this status. And as the term suggests the Journeyman was expected to travel to other places to find work in their trade and to further their education. The Master presented the new Journeyman with his kit of tools (that had most likely been made by the apprentice) and he was sent off to seek his fortune. In Europe this system was highly developed and controlled by the Guilds. The Guilds had strict rules and awarded certificates of apprenticeship, Journeyman and Master. After a period of time a Journeyman could apply for Master's papers by proving themselves to a board of Masters and submitting a "master piece". Only a Master with papers was permitted to take on apprentices and to teach the trade. In the Americas there was never an entrenched Guild system and the requirements for being a tradesman varied greatly or was not regulated at all. There was such a lack of skilled crafts people in the early days that anyone with skills could set themselves up in business.

The old apprentice system had its advantages and disadvantages. At one time it filled a need. A good Master would teach the apprentice everything from the math needed to perform his tasks to business methods. However, occasionally there were abuses and Masters would use their apprentices as cheap labor and fail to teach what was required or they would mistreat the apprentice. This happened often enough that most laws regulating apprenticeships had to do with these abuses. On the other hand the apprentice may not have had a choice of trades and could find themselves bound to be a laborer in a trade they had no aptitude or interest.

The old apprentice system disappeared with slavery, indentured servitude and child labor. The laws that freed slaves and indentured servants made it difficult or impossible to enforce an apprenticeship contract. Today there are programs titled apprenticeships in some trades but they are generally not regulated or are specific to an industry, business or trade union. They are no longer a work for education exchange but are generally a measure of experience upon which pay scales are based. In most of these arrangements the "apprentice" has gotten their education from public schools and trade schools before going to work.

Today there is no true apprentice system.

Schools, both regular liberal education, higher education, colleges, universities, and trade schools have replaced the old apprentice system. The labor exchange has been replaced by taxes supporting public education and fees paid for higher education and trade schools. The medium of education and training is now almost exclusively cash. Not only that but in the U.S. the tax system requires income taxes to be paid by the "employer" in some labor exchanges. At a minimum they want taxes covering the value of room and board that may be provided to the "apprentice".

In Europe, notably Germany, there is still a system of certifying craftspeople and you can still get Journeyman and Masters papers there. But this is becoming more along the line of our "industrial" apprenticeships.

Blacksmiths and Shops Today

Although blacksmiths in general do not make a great deal of money (you have to LOVE the trade), their shop time is often worth more than $100/hour US. Like most small business people, their day has many nonproductive hours required to operate the business and to sell their work. Hours in the shop training someone are valuable shop hours that may have otherwise been spent producing work. Expecting a skilled craftsperson to teach someone without proper compensation is presumptuous at best.

You hired him, YOU fire him!

Unskilled "apprentices" can be a huge problem in blacksmith shops. A modern blacksmith shop is often the equivalent of a modern machine shop and welding shop with the addition of many rare and antique tools. Most of this equipment has the built-in capability to be self destructive as well as lethal. No matter what your current education level, if you do not UNDERSTAND machinery and shop safety you can be a huge danger to yourself, others AND to the very valuable machinery. This problem is compounded by the fact that many very good blacksmiths are not nearly as well trained on this equipment as THEY should be. They get by because they at least respect the machinery and know what it cost them. The result of having an unskilled worker in the shop can be a swath of destruction that the smith may never recuperate from.

So the question IS.

What valuable skills are you bringing to the blacksmith shop?

Your previous years of education may not count for anything in a blacksmith shop. Almost all shops have gas and electric welding equipment (MIG, TIG, Plasma). Have you taken a full series of welding classes? Although many smiths do not use arc welding in their work they will almost always have electric welding equipment for building fixtures and maintaining their shop. Do you have any industrial safety training?

Architectural shops deal with drawings and specifications including the need to take accurate field measurements. Do you understand measurement dimensioning and tolerancing sufficient to be trusted to take dimensions without someone double checking your work? How well do you draw? Read drawings? OR. . are you willing to spend a dozen hours or more doing menial boring work at minimum wage or less in exchange for an hour of your "masters" time? In the more technical areas of smithing such as bladesmithing the top people have masters and doctorates in metallurgy and engineering PLUS years of self study in their field. Have you looked into all the classes that are applicable to the specialty of your interest?

An amazing amount of blacksmithing is repetitive production work. Look at a large piece of architectural work. It may have hundreds of pickets scrolls or leaves that are all alike. It may take someone days or weeks to just cut the stock to length. After each piece is forged by a skilled smith each piece may need trimming, deburing and finishing. Assembly often requires a LOT of brute force heavy labor. Cleaning and painting is a HUGE part of the job. Installation time can mean hauling a ton or so of tools and equipment on and off a job site every day for a week. Every shop needs low cost laborers that don't dream of being artists or who want to play with the machinery. This is a fact of life. So even if you get into a shop, they may not want to move you up. . .

The Good News

In North America and many other parts of the world most blacksmiths are very sharing and willing to give lessons. There are also ABANA chapters in almost every state of the US as well as in Canada and New Zealand. In Britain there is the British Artist Blacksmith Association and in Europe there are more organizations. Your local organization is the best place to find out about lessons and where to get fuel and tools.

There are also more books on the subject of blacksmithing than ever before. New books are constantly being published and old books are being reprinted. AND there are the many web sites like anvilfire that have how-to, plans and information.

In North America there are now more blacksmithing schools than ever. Most are operated seasonally and fill up quickly. Check the ABANA schools list and register early.

The ABANA Journeyman program: A Journeyman is much different than an apprentice. A Journeyman may have skills far beyond what you expect for a "starter" position. Check the recommended skill levels carefully on the ABANA web site. A FEW shops will take on a "Journeyman" at minimum wage or so, depending on the needs of the shop and the skills brought by the, Journeyman. It is a tough program to get into and get placed. It is a voluntary program in which both sides need to work out the details. ABANA just sets the guidelines. Documentation of all your blacksmithing skills may be needed. Consider the difference between where you are now and the ABANA Journeyman level.

So how do you get to this level? See our Getting Started article. You take trade school welding and machine shop classes (perhaps your college or University has some of these), then you go to the various blacksmithing schools . You go to ABANA-Chapter meets and work on your own. Along the way you may meet someone willing to take you on in their shop (probably without pay). It is not easy and requires a lot of self study.

Selected Q&A

I am a soon to graduate college student with a great interest in blacksmithing. I have dabbled for the last few years, and would like to find a paid apprenticeship. I am a fast learner and a hard worker. Any ideas?

Scott - Sunday, 10/28/01 07:59:26 GMT

Paid Apprenticeship: Scott, That phrase is an oxymoron. Classic apprenticeships were an education and included an apprentice "fee" on top of 7 years servitude in a binding contract. That was the value of this highly desirable education. I am sure your current education has cost tens of thousands of dollars ($100K +)? So why don't you expect to have to pay for further education????

The classic apprenticeship is a thing of the past.

NOTE: Some businesses have what they call apprenticeships that start at minimum wage. Usually these positions require that you have finished a general education plus specific courses covering the position. This is often more of a trial position than an apprenticeship. Other businesses will pay to put you through school while you work. However, while working full time AND going to school you will only be paid a minimum wage. Businesses that do this are generally desperate for trained employees and rather than training them in-house they have arranged for the local school system to do the job to their requirements. This takes the burden off the business and takes advantage of a taxpayer supported school system. These types of deals are made with large employers and would not apply to a small shop (unless it just happened to be in the same business).

Consider the offer I made last summer (2001). I needed someone to mow a 2 acre "lawn" (jungle actually), sweep shop, clean and de-rust old machinery, dig ditches, do a little construction type work. Lots of menial tasks. In exchange, I offered a place to stay (primitive) and meals. Access to my library and shop (within limits) and a couple hours of my time a week in actual blacksmithing instruction (on top of the instruction necessary for the other jobs). My time was based on a ratio of 12 or 14 to one. There were also some other perks. Trips to a private museum and other blacksmith shops, local ABANA-Chapter meets and historic sites. The "apprentice" would have also gone home with tools and equipment made as apprentice projects. Punches, tongs, swages, forge. . .

This is what I could afford in a apprentice deal. The apprentice got an education in many areas other than just forging. Much of the value to the apprentice depended on how his or her time was applied. It would take a year to read my library of smithing and metal working references much less study them all. Forge time was open ended with fuel and materials provided. It was a worthwhile opportunity that had costs and benefits to both parties. And, it is probably similar to what you will find in "apprenticeship" offers from others, until you reach that Journeyman level.

Sunday, 10/28/01This offer is still open to the right person. Write to me.Position filled for 2003-2004

Position no longer available. 2005 -

- guru

Hi there.

I am very interested in becoming a blacksmith but have had very little luck in finding a local teacher. Could you please let me know whereabouts I would locate someone in SOUTH AFRICA or where else I would be able to study from. I am desperate! It is truly something I want very much to do. Many thanks, and I look forward to hearing from you soon.

Carla - Friday, 11/16/01

South Africa: Carla, we have several regulars from South Africa that visit anvilfire but it has been a while since any have posted. Those that I can think of are knife smiths. But there are many others that read our forums and do not post questions or comments.Post your message on our V-Hammer-In. This page (the guru's den) is archived weekly but the Hammer-In is archived monthly so your message will be seen for a longer time. Re-post your message if necessary. Someone local to you may see the message and help you find the teacher you are looking for.

- guru - Friday, 11/16/01

References and Links