|

There is no free lunch. Nobody is going to teach you all the details of a craft just because you ask.

You may be VERY VERY lucky and find someone willing to share their hard earned knowledge but they will expect YOU to have done your part.

In the first half of the twentieth century there were very few books on the craft of blacksmithing and none on bladesmithing.

About the time the craft of blacksmithing was dead people became interested in the hand crafts including blacksmithing in great numbers.

The result is that there are now many very good books on the subject of blacksmithing, bladesmithing and knife making.

Many of the old references that were impossible to find are also now in reprint.

This means that there are now more books on these subjects than at any other time in history.

Lack of available references is not an excuse.

If you have not found at least a few of these books and STUDIED them,

then you are wasting your time,

my time,

and certainly anyone you ask about teaching you.

To have not done your best to study these subjects and then expect a master of the craft to hand feed this information to you is an insult.

Some of these books can be found in libraries, others can be borrowed by your library on inter-library loan (ILL).

But a few will need to be bought. Yes, they cost money. But these are not expensive books.

Most are written better than any regular text book and cost much less.

If you cannot afford a few books to study then you are wasting your time.

You cannot work without tools and these books are tools.

Most that come to us asking how to make a sword are quite naive about the subject.

From this point onward there is no excuse for you to be naive or to insult those you wish to learn from by not having researched the subject.

We have listed here many books on the subject of blacksmithing and bladesmithing and we have reviews of most of these books.

Obtain them. STUDY them.

You have NO excuses. Naivety is no longer allowed.

RESOURCES: The death of naivety. The end of innocence.

<<< Click this link!

Zero Tolerance

We have had several questions about making swords or daggers as school projects.

In most American schools there are currently "zero tolerance" policies regarding guns and knives including plastic or toy guns and knives.

This extends to anywhere on school property including parking lots.

It is not uncommon for weapons to be found and confiscated from vehicles on school property and the driver expelled from school.

Have you asked your principal and guidance counselor about your project?

Have you considered another less controversial metal working project?

Maybe a defensive device such as a shield, helmet or armor?

Costs of Education

"I want to find a Master Swordsmith to teach me how to make a sword."

We get the "who will teach me" question above on a regular basis from people that have not looked for or read a single book on the subject.

They have never suggested that they were willing to PAY for lessons.

Education costs money everywhere else, why not in this case?

We had one questioner on our forums bitch and moan about the cost of the books we had recommended (less than $100 worth).

Maybe he thought that if he claimed poverty long enough that someone might GIVE him a book to shut him up.

His excuses were water thin.

He had not been to the library and after being pointed that way made more excuses.

He was looking for charity and had demonstrated clearly that he was not worthy of it.

Don't be this person.

Books as already mentioned are a cheap part of learning this trade.

Not only are many how-to and educational texts, they are often necessary references listing steel specs, heat treating information and other things too numerous to remember in detail.

Books are tools that are just as necessary as a hammer to a smith.

For the average self employed craftsperson to make a living in North America in 2003 they must charge a shop rate of at LEAST $100/hr.

I will not go into the detailed breakdown but if they charge anything less then they can (and do) end up making minimum wage or less.

A master craftsperson should be able to charge more.

Their education is that of a doctorate, a Phd. or equivalent.

No matter how it was obtained, their education cost them time, their life's blood, AND money.

So why should anyone think that they should be willing to take someone into their shop to teach them for anything less than what they normally must charge to make a living?

Oh, so you think working in the Master's shop should offset the costs. . . HOW? Sweeping and cleaning?

Lets see, a janitors rate of $10 hour vs. $100 hour. . if you worked full time for two weeks and do not incur any costs (distractions, breakage, use materials) then you might have earned one full day of the Master's time.

Just how much cleaning and sweeping do you think there is to do?

The fact is that even at a 10:1 ratio the craftsperson probably cannot afford to have you in their shop.

Materials, even cleaning tools and supplies cost money.

When the cleaning is done then what?

Painting, maintenance, carpentry work?

These are skills that the average apprentice does not have.

The materials for these cost more and like the cleaning the amount to be done has a finite limit.

Apprentices also tend to break things and damage tools due to lack or experience and often lack of respect.

There are sound financial reasons why schools with a dozen people in the classroom dividing the costs among them have replaced the old fashioned apprenticeship.

Think about that $100/hr before you ask a professional to give you individual lessons.

Think hard about how far the education from a couple hundred dollars worth of books will go.

A letter and response to a reader that thought an education in sword making should be free in order to preserve civilization.

Experience

"I've never done any metal work and I want make a sword."

This may sound naive but it is a real question that has been asked here more than once.

It is almost as bad as the fellow that described the entire forging scene from Conan the Barbarian, then stated "I know all that, now what?"

He knew nothing. Much less the difference between fantasy and reality.

The craft of the Swordsmith is one of the most difficult and demanding of blacksmithing skills.

It requires both physical and mental discipline.

It requires many hours of practice at a wide range of hand skills such as forging, carving, filing, engraving and finishing.

It requires a practiced artistic eye and technical knowledge in a wide range of subjects.

Like anything else, you do not start at the top.

If you have never worked at the forge then you have no business asking for lessons at the top of the skill level.

Forging takes many hours of practice making items over and over until you can make every one perfectly.

Using a file a saw properly, or drilling holes are skills that you do not need to learn from a Master Swordsmith.

But they ARE skills that you need to not just learn, you should master them.

Forging Damascus, laminated steel or Japanese blades is mostly forge welding.

Welds are made over and over and every one must be perfect.

This is a skill that the self taught can learn and practice until perfected without bothering a Master about basic lessons.

Traditionaly in almost every culture the labor of sword making was divided at a very early date.

An Ironmaster made the steel. The cutler forged, ground and heat treated the blade.

Later these were each specialized tasks further dividing the labor to bladesmith, grinder and heat treater.

The "hiltsmith" made the furniture and the grip.

A scabard maker made the scabard.

A presentation piece would probably go to an engraver or jeweler to have more decoration added.

As many as eight seperate craftsmen and an untold number of helpers may have worked on a single sword.

Today, due to economics, most makers do it ALL. This means that they must be skilled in many crafts.

A few sub out heat treating and most sub out engraving. Making scabards is still a specialty.

This is not the only item that was made by many.

Violins require three experts in entirely different crafts, the violin maker, the string maker and the BOW maker.

Stradivarious made what are considered perfect violins.

But bows are just as finicky and a poorly made bow can debase the finest instrument and the best bow can raise a mediocre instument to greatness.

Stradivarious did not make bows, just cello's, viols and violins which ALL required a fine bow.

Specialists are often required to make perfection.

Options

I always recommend options to making the real thing.

There are many reasons.

One is that making a sword is a BIG project involving more than one specialty.

The options are not nearly so big a project, nor as technical and when done you may be glad you didn't start on a more involved project.

These projects are not a waste of time. Each one requires skills needed to make the real thing.

They can be a learning experience as well as saving you a lot of grief and expense in the long run.

The primary reason for suggesting options is that sword making and bladesmithing are the highest skills of the blacksmith or metalworker.

Besides the basic metalworking skills the bladesmith needs to understand the art of the design of the blade from both an artistic and engineering standpoint.

The bladesmith must also have a thorough understanding of metallurgy and heat treating.

Making the furniture (guards, grips pommels) are often an art into themselves requiring the skills of a jeweler, knowledge of casting and working non-ferrous metals.

To do a decent job takes years of education and study as well as the expense of setting up shop.

Today the top men in the field have masters and doctorates in metallurgy and then spent years studying the practical aspects of actually making blades.

These masters of the craft will tell you that they still learn something new every day.

And the most important reason,

if you are one of the many that has made nothing else of metal then a sword is NOT the place to start,

you really should start with a simpler project.

Please read through the options.

Many of the techniques described apply to other methods and all apply to making a complete blade.

- Wood Sword

- Aluminium Wallhanger

- Stainless Steel Wallhanger

- Cooking Knife

- The Real Thing

Option 1: Wooden Sword / Knife

To make a model sword not a practice weapon.

If you are a beginner this is good practice in fitting the pieces together.

If you cannot make good fits in wood then metal is out of the question.

Wooden models are often made by professional bladesmiths.

The prototypes of the blades made for the Rambo movie are in the Knife Museum in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

These were carved in one piece from a pine 2x4 (framing lumber).

Several were made and submitted to the director of the movie before the actual blade was made.

If top professionals do it, then why shouldn't you?

A sword is nothing more than a BIG knife. The parts are all the same.

I suggest making knives first because it is much easier and if you screw up you have lost a lot less time and material.

This is also somewhat true in making a wooden model.

Hard maple is one of the best woods for making almost anything from musical instruments to furniture.

I recommend it for this project.

There are other dense grained hardwoods that will also work such as cherry or walnut.

A good piece of pine will also work but in fact the soft woods are harder to fit and work well than hardwoods as they do not file well.

Tools Needed:

- C-clamps

- Table or work bench (this is light work and a kitchen table will do)

- Band saw, jig saw or sabre saw.

- 3/16" or 1/4" wide mortising chisel.

- Files and Rasps (several types)

Four in Hand (multi-purpose file/rasp)

Nicholson #39 or #40 Cabinetmakers Rasp

12" Mill file bastard cut

10" Flat bastard cut

8" Round rough cut

- Sandpaper (Optional may be replaced by Scrapers)

120 grit cloth backed (belts or sheets)

240 grit cloth backed (belts or sheets)

- Sanding Block(s)

- Hand Scraper with burnisher (standard wood working or hand made).

- 1/4" Drill (hand or electric), 7/32" and 1/4" bits.

Optional tools can include a belt sander/grinder.

A traditional Japanese clamp bench can also be substituted for the C-clamps but is not as flexible.

A Jeweler´s Saw and bench pin or fine wood working scroll saw can make fitting the guard much easier.

NOTE: I have carved similar items in significant detail starting from a green log using nothing more than a hand axe and a pocket knife.

The tool list above is for the non-primitive wood worker to give them the best chance at producing the final project.

If you have the skills or want to study primitive wood working seperately you can do with much less.

Materials:

You will need to obtain some hard maple or other suitable wood.

If you can, order a 1/4" thick board.

1" wide is suitable for a reasonable knife or dagger and 2" for a big Bowie or sword.

If you only find thicker stock then you will need a way to saw it (table saw or band saw).

Optionally if you want to make this a classy project you may want some colored fruit or nut wood for the guards and grip or stain them individualy.

Method:

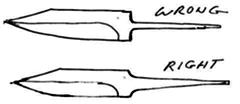

[Tang Layout Drawing]

Starting from the 1/4" slab you will need to layout the shape of the blade in pencil.

Be sure to have large radii where the tang attaches to the blade. I recommend 1/4" minimum.

Sharp corners cause stress concentration and result in blades that break at the tang.

The longer the blade the heavier the tang should be.

Profiling: Saw the shape including the tang using a bandsaw, scrollsaw or jigsaw.

This is called profiling and is no different than making a steel blade by the stock removal method.

However, you will need a slow speed metal cutting saw to blank out a blade in steel.

Sometimes (rarely) profiling is done by grinding steel and a belt sander/grinder can be used for either wood or steel.

After the profile is rough cut it is finished by filing.

The smoother the tang surfaces the less likely they are to be a source of cracks and possible breakage.

Remember, if you have difficulty fitting the wood, metal is much more difficult.

Shape the blade by rasping, sanding/grinding and scraping.

If the blade is double edged draw center lines on the sides and edges to work to.

Wood cuts very quickly and it is easy to make a mistake. Plan on doing the finish shaping with a

hand scraper.

A pocket knife or draw knife can substitute for a scraper but scraping is hard on thin blade edges.

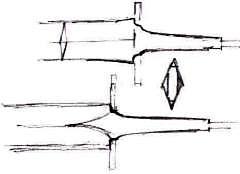

[ Diagram of Knife Parts ]

Saw out the guard from a waste piece of the blade stock or other hardwood.

Drill two starter holes as shown and then cut out the space between with a chisel or jeweler's saw.

Carefully fit the guard to the radius seat on the tang.

A well fitted guard has no visible gaps at the tang joint.

Block out the pommel from a piece hardwood. Note that final shaping may be done in assembly with the grip.

Drill the tang hole as shown. Fit the pommel to the end of the tang.

It should be able to slip on a little farther than where the end of the grip is going to be.

Normally the pommel is riveted onto the tang or threaded on. In wood we will glue or wedge.

The grip is made from two slabs of hardwood.

The hole for the tang will be carved (inlet) into the two pieces and then they will be glued together making a tapered rectangular hole that fits onto the tang snuggly.

Carefully block sand the front surface of the grip until it must be tapped onto the tang to seat against the guard.

Block sand the back end of the grip flat until it fits cleanly with the pommel.

Shape the grip with a rasp and files.

Finish the front then assemble and work the grip and pommel together with files and sandpaper to make a perfect fit.

Disassemble and finish sand the grip being carful not to round the corners that fit the guard and pommel.

The finished sword or knife can be lacquered of finished with hand rubbed varnish before assembling.

The assembly can be done with glue or by wedging the pommel.

In fine blade making epoxy resins are used to fit grips making a perfect permanent fit.

On this project any glue may be used if desired.

Using clear epoxy would be good practice as it is tricky to keep it off finished surfaces.

Option 2: Aluminium Wallhanger

Aluminium is light and strong. The aircraft alloys (2024 and 6061) are nearly as strong as mild steel.

Alloy aluminium is easy to cut and finish.

A fine aluminium blade can be made with nothing but hand tools (hacksaw, files, sandpaper) similar to the tools used to make a wooden model.

It can easily be brought to a mirror finish by hand using fine sand paper and paste polishing compounds.

It does not rust.

The techniques learned apply to working ferrous and other non-ferrous metals such a brass and bronze.

This is a project that can be done in an apartment or bedroom workshop.

Although an aluminium blade is primarily a "wallhanger" (a show piece), many of the blades seen in movies are aluminium.

Why? For many of the reasons above.

They are strong, lightweight and relatively inexpensive to make and look good.

Not rusting makes them low maintenance.

When used for swordplay (acting, demonstrations, practice) they have very round dull edges to prevent cutting someone as well as damaging the blade.

Being light makes them easier to wield.

In the real 21st Century world an aluminium sword is just as lethal as a steel sword.

Although lighter than bronze an aluminium alloy blade is nearly as strong and can take about the same edge as a bronze sword.

Remember the Bronze Age? The thousands of years leading up to the Iron Age?

All of the slaughter in the Old Testament of the Bible and in most of the Greek tales (Homer, The Odyssey) occurred during the Bronze Age.

So an aluminium sword is not a joke or a toy.

Aluminium is a "white metal", it looks more like silver than steel.

However, many people cannot tell the difference between polished aluminium and plated steel.

Although it does not rust it DOES slowly oxidize.

But it takes years for a polished aluminium surface to oxidize to a dull surface.

An aluminium sword can have aluminium, brass or steel furniture.

You will have scraps of aluminium to use for furniture (the guard and pommel) but if you wish and want to spend the money you can use other metals. The methods of shaping and fitting are the same.

The grip can be made using any suitable method. It can be solid metal, wood, bone, synthetic ivory, leather wrap, wire wrap, plastic. . .

I have made wallhanger grips out of auto body putty then carved and painted it to look like bone.

Wood can be done the same or finished natural. Small bits of exotics such as Ebony, Rosewood or Cocobolo could be used.

Tools Needed:

- Bench Vise or clamps

- Table or work bench

- Hacksaw or metal cutting band saw.

- Files (several types)

12" Mill file bastard cut

10" Flat smooth cut

8" Flat smooth cut

12" Square bastard cut

10" Flat aluminium cut

8" Half Round aluminium cut

10" Round rough cut

- Sandpaper

120 grit cloth backed (belts or sheets)

240 grit cloth backed (belts or sheets)

180 grit Wet-or-dry (pack)

320 grit Wet-or-dry (pack)

- 1 can 3M Orange buffing compound.

- Sanding Block(s)

- Hand Scraper with burnisher (standard wood working or hand made).

- 1/4" Drill (hand or electric), 7/32" and 1/4" bits.

Optional tools can include a belt sander/grinder and a small lathe (to turn the pommel).

A traditional Japanese clamp bench can also be substituted for the vise but is not suitable for sawing.

A Jeweler´s Saw and bench pin or fine wood working scroll saw can make fitting the guard much easier but this is the limit of their capacity in non-ferrous metal and 1/4" is probably too much in steel.

The jeweler's saw can be used to make cutouts (piercings) in the blade and guard as well as making inlays for the grip.

You may want a wider variety of files but you can also do with less.

For this project one of the large coarse files or aluminum cut files will do.

Materials:

The suitable aluminum alloys are 2024-T6, 6061-T6 or 7075-T6.

6061-T6 is the most commonly available. 7075-T6 is a very hard grade.

2024-T6 is used for 90% of an aircraft's structure and is a little soft.

The "T" values are the temper (hardness).

Aluminium is hardened by working (rolling, stretching) and age hardening in an oven.

0 is the softest and 7-10 the hardest.

Hard aluminums are best because they cut easier and do not clog cutters and abrasives as bad as soft.

They also take a better finish AND for our purpose are stronger and springier.

A piece of 1/4" x 1-1/2" or 2" will only cost a couple dollars per foot.

Order a piece 48" (1.2m) long.

Method:

This is a "stock removal" method.

It could be done with a large belt sander and coarse belts but is not too difficult by hand.

The entire blade can be roughed in a day or two.

Note that aluminium and brass can quickly clog or load grinding belts. Special non clogging belts are available and coolant helps reduce clogging.

NEVER grind aluminium on a bench grinder.

The wheel will clog instantly and require dressing before regular use.

Starting from the 1/4" slab you will need to layout the shape of the blade using a fine marker or a "Sharpie".

Be sure to have large radii where the tang attaches to the blade. I recommend 1/4" minimum.

Sharp corners cause stress concentration and result in blades that break at the tang.

The longer the blade the heavier the tang should be.

Since this is going to be a long sword the tang will be nearly as wide as the blade and taper to square (the same width as thickness) for about the last 1-1/2".

Saw out the blank then file smooth (profile the blade).

At the tang leave extra material at the radii so that the finished shape can be filed smooth.

File the edges of the blank clean and square to remove all saw marks or divots.

Layout the blade's center line on both sides and both edges.

This can be done with dividers and a straight edge or a cabinett makers marking guage.

I would lightly scribe these lines but they can also be applied with a sharp felt tip marker.

Start filing! The goal is to produce smooth flat facets. Use the coarse files until the shape is complete.

Leave a flat edge on the blade between 1/16" and 1/8" wide.

Try for a nice crisp center bevel on the sides of the blade.

Do not sharpen or round edges with the coarse files.

File out all the coarse file marks with a smooth cut file OR use the scraper.

Remove the smooth file marks with the scraper.

Hold it at about 45° to the direction of the stroke. Alternate the angle between strokes.

This will flatten as well as smooth.

NOTE: DO NOT use the scraper parallel to any of the file marks.

This will result in bumps or ripples that are very hard to get out.

It helps to file in alternating directions so that you produce an even cross hatching at about 30° angles.

When scraping work at angles different than the file cuts.

At this point the object is to make flat smooth surfaces with sharp cornered jewel like facets.

This helps keep the lines straight and accurate.

Rounding comes last.

IF you did a very good job with the scraper you can jump to the 180 grit Wet-or-Dry paper.

Use it wet and on a sanding block or stick.

Continue to keep all the facets flat and with crisp sharp corners.

A sanding block can help prevent rolling of corners.

Work the entire blade until it has a smooth grey finish and no evidence of filing or scraping.

IF you did NOT do a very good job with the scraper or did not scrape then start with the 120 grit cloth.

Use it wet and on a sanding block or stick.

Continue to keep all the facets flat and with crisp sharp corners.

When the entire blade has an even finish then change to the 240 cloth.

Once finished with the 180 paper or 240 cloth it is time to radius the blade edges.

Leaving a flat facet on the edge of the blade it will look sharp.

Optionally you can use a smooth file to create two 45° chamfers which result in a sharp looking square edge.

Do not try to make it sharper.

Rounding the edges is recommended if the blade is to be used in sword play. Otherwise it will nick and ding easily.

Start by filing smooth even 45° chamfers on the square edge that leave a flat the same width as the chamfers.

Then using 180 grit and a sanding block remove the file marks and break the resulting corners. The idea is to make a smooth accurate radius.

Once the corners are broken you can hand sand the radius to a smooth round edge.

Using 320 grit paper wet finish the flats and edges by hand.

Smoother paper can be used before polishing but I have found little or no advantage.

Polishing can be done on a sewn cotton buffing wheel using Tripoli OR by hand using 3M Orange buffing compound.

Dip the folded corner of a rag into the buffing compound and apply to the blade rubbing lengthwise.

As the compound dries refresh it. Do not apply to more than the area you can work at one time (about 1 foot of blade at a time).

Continue to use the compound wet until it seems to do no more good.

Then polish with the small amounts of the worn dried compound in the rag.

Change to a smooth clean rag and polish off the remaining compound dry.

A minuscule amount of worn compound off the surface of the blade will be enough to finish the surface to jewel like brilliance.

Saw out, shape and fit the guard from the material of your choice.

To make the hole for the blade layout a rectangular hole the size of the tang on the back of the guard.

Drill two 1/4" holes to start. Then file the hole square using the square file.

Radius the front of the hole to fit the blade shoulder radius.

Fit this area carefully. It should fit tight and not have any visible gaps.

It is one of the most critical quality areas of a custom made blade.

A perfect fit in this area is one mark of a professional.

Finish and polish the guard the same as the blade.

The pommel is usually made of the same material as the guard.

Drill a 15/64" hole in the pommel and then file the end of the tang to a snug fit.

IF the grip will be a hard material and the pommel fitted last the round shank should have a little extra length.

IF the grip will be added after the pommel then the tang needs a shoulder to position the pommel.

There should be about one diameter of extra tang end.

Countersink the hole in the end of the pommel lightly.

The end of the tang is upset (bradded) into this chamfer on final assembly.

The end is then finished round or flush with a file and finished to match.

The Grip if solid hard wood (walnut, ebony, exotic) is made the same as the Option 1 Wooden Sword grip and fitted to the pommel the same way.

However, care must be taken when finishing wood and metal together.

The wood cuts much easier than the metal and shaped tools fitting the cross section work best at the joint.

A wood grip is best bedded in with clear epoxy as the tang is riveted making a tight permanent assembly.

Option 3: Stainless Practice Sword or Wallhanger

This project can also be carried out in mild steel.

The point is to make a practice sword from ferrous metal by forging, finishing and fitting all the parts exactly as you would a real sword without working high carbon steel and needing to heat treat it (harden and temper).

The furniture on this sword should be brass or stainless.

You have the option of fabricating, forging or casting the furniture.

Casting brass is a whole new world of tools and techniques but is also one of those skills practiced by most armourers.

I recommend learning casting as a separate craft at another time. So we will describe a fabricated guard and pommel.

Details to follow. . . . . (basically same as the above with forging as an option for some shaping.)

Option 4: Carbon Steel Knife.

If you cannot make a small high quality cooking knife then why do you want to try to make a sword?

A blade 4 times bigger than a kitchen knife or a Bowie is 20 times harder to make.

If you find heat treating a 12" blade is difficult then a sword may be impossible with your skills and equipment.

A small blade is a step in learning all the processes for making a large blade.

Details to follow. . . . .

Options 5 - 6: The REAL thing.

If you skipped options 1 through 4 then you have missed all the prerequisites.

We'll assume you are an experienced craftsperson with all the skills described above.

There is more than one way to make a sword.

Forging, stock removal or Damascus (laminated steel) which combines both techniques.

Then there are options to the Damascus.

You can forge your own billet, you can purchase a Damascus blank or you can buy a finished blade and fit furniture to it.

Many makers use blanks made by others and some of the pre-finished blades are less expensive than blanks. . .

In each case you must have a design in mind. You may want to have made a prototype in wood.

If you have completed option projects 1 through 3 then you should know how to design and layout your blade.

If you have completed option projects 3 and 4 you should know how to fit the furniture to a steel blade and have some idea how you want to proceed from this point.

So all that is left is to learn to do is make a long blade rather than a short one.

The decision as to how to make the blade is yours and yours alone.

The biggest difference between making a knife and a sword is the equipment necessary to handle the length of the blade.

You CAN finish any blade with files, hand scrapers and natural stone.

If you prefer to use machines the grinding equipment to do simple finishing is nearly the same for a forged blade as for a stock removal blade.

Powered grinders have been used for centuries.

To use machinery rather than ancient hand methods you will need a good belt grinder.

Where 2" (50mm) wide belts are suitable for most blades it is recommended that you use a 6" (300mm) wide belt for sword making.

The machine cost difference is considerable.

Forging a sword does not require a long heat.

If you heat the entire length of a sword to a red heat it becomes limp and hard to handle.

Forging is done in short sections and can be done in most forges.

A long trough forge is most convenient because there is room for the extra length.

For heat treating you need to heat the entire blade evenly at one time.

This can be done two ways, horizontally and vertically. Both methods require a long forge or furnace.

If heated horizontally the blade must be carefully handled to prevent bending under its own load.

The blade must be supported carefully between furnace and quench tank.

If heated vertically the blade can be lifted with a hook or by the tang and there are no bending loads on the blade.

However, to get an even heat the furnace used must have good circulation.

Salt pots are often used for these long vertical heats because of the more uniform heating and lack of oxidation.

Sword Myths/Fiction:

- Blood does not make a superior quenchant (an old myth).

- Neither virgins or slaves have been used to test swords (that is a children's story).

- You cannot chop a machine gun barrel in two with a Japanese sword (modern myth).

- Ancient steels were not superior to modern alloy steels (another modern myth).

- Atlantis was not in the Atlantic.

The story of Atlantis was based on rumors of the demise of the Minoan island culture

in the Mediterranean by a volcanic eruption.

The story was handed down by Egyptians to Plato who turned the little truth into a myth.

- Adamantium is a fictional comic book element without any basis in reality (like Kryptonite).

It is just another "Unobtainium".

- Mithirl (J.R.R. Tolkien) another MYTHical metal.

- You cannot cold forge a sword from a leaf spring (modern web myth - parody).

Hype:

The forging scene in Conan the Barbarian is Hollywood fiction, all the methods shown are imaginary and/or do not go together.

Steel sword blanks are not cast, that is a Bronze Age method using copper alloys not steel.

Nobody forges on an an anvil with a flammable liquid on it (but some blade makers use water).

You cannot compare "sunrise red" to a sunrise and snow is not dense enough to be used as a quenchant.

It is FICTION. It is great fun but it is NOT real.

Highlander:

You cannot chop into a concrete column with a sharp sword without seriously damaging it.

You cannot chop steel railings or beams in two with a sword (ANY sword).

Swords do not make showers of sparks when slid against other items or other swords.

Titanium:

Titanium is NOT a blade metal.

It is not intrinsically sharp or hard as a recent TV commercial for razor blades indicates.

That is more Hollywood hype and bad science written by advertising executives that know nothing of metallurgy.

Titanium nitride. TiN, used to coat cutting tools, is stable well past the melting point of steel.

But its properties are only suitable to use as a very thin coating over a harder material.

It increases wear resistance.

The use of Titanium in steel is usually limited to VERY small amounts used to scavenge nitrogen from the

melt when using boron as a hardenabiltiy agent.

Titanium itself does not make an appreciable difference in alloying the steel.

Those selling the superior properties of "Titanium Steel" are playing on the customer's ignorance and the sexiness of the word "titanium".

Questions and Answers:

I want to learn to make traditional Japanese blades

The first thing to learn is to forge weld, forge weld and forge weld.

Practice making stacked billets then cutting them apart every half inch or so and inspecting the welds.

Every one must be perfect. A single inclusion is failure. Then weld the pieces back into one and repeat the process. When you can do this all day your welding and hammer skills may be ready.

The traditional method of making Japanese blades starts with smelting the iron then making the steel in the forge.

It is a long slow process.

Many make Japanese style blades but few make truly traditional blades.

In the West most makers start with stock iron or steel and then blend them into a something similar to the traditional material.

But it is NOT the traditional material or method and therefore the RESULT is not traditional.

Much of the traditional process requires helpers to work as strikers.

Since nobody in the Western world can currently afford that kind of labor except for demonstration purposes, machines are used.

Most shops use power hammers, forging presses or rolling mills.

So what is traditional? Who's traditions? When?

- guru

How long did it take to make a sword in medieval times?

In medieval times having a blacksmith make a sword all by himself would be as common as having a heart surgeon today do an operation all by himself. A single person blacksmith shop is an oxymoron in historical times.

Also why would a trained smith waste his time grinding and polishing and hilting a sword? Having the capital tied up in equipment that you did not use full time was not likely either---grinding was usually water powered and that means a lot of building and equipment with high maintenance costs. ("The Mills of Medieval England" discusses the high costs of running water powered equipment; or the Guru can speak of maintenance costs of working where the floods occur...)

The typical work flow was that the smith with probably 2 strikers would forge the blade. It would be sent out to a different shop for grinding and they would send it to a third for hilting and a fourth for making the scabbard---*THAT'S* the reality. Often the hilters would be the "primary contractor" and sub out the rest of the work.

Fiction hardly ever gets it right as the reality gets in the way of the story...

Don't forget that when you buy the metal from the merchants who bought it from the smelters that you have to test each piece for quality and carbon content...

As for time: pattern welded or not? Does the smith have to carburize his own steel or can he buy natural steels or pre-carburized metal?

(see the steps used in traditional Japanese blade smithing above.

The basic forging---with help---is not too tedious ranging from a couple of hours to a couple of days depending.

Grinding will take much longer than in modern times---though the blades being forged to shape will help some. Say a couple of days to a week depending on the equipment and the complexity of the bladeshape. Hilting will take some time as the pieces will have to be forged and then filed/ground/polished and then *FITTED* to the blade. I would expect it to be a couple of weeks if it's a fancy set up---more if engraving and the setting of jewels is required. Scabbardmaking will take a week or so *if* the material is to hand. There will always be special cases in both directions. and Where and When makes a big difference!

Now assuming hed did it alone: 7 years apprenticeship to the smith, 7 years apprenticeship to the grinder/polisher, 7 years apprenticeship to the hilter and 7 years apprenticeship to the scabbard maker---so *if* he had access to all the equipment I would say he would start off with needing 28 years to maike a sword on his own...

- Thomas P - Tuesday, 11/15/05 12:07:28 EST

I read somewhere that a Japanese bladesmith with strikers hogged out and shaved (with a push-shave, a "sen") about five blades a month and of the five, he usually kept two.

The reason given was that the throwaways were either physically flawed or that they did not "feel right" when swung.

The keepers were sent to the polisher.

- Frank Turley - Wednesday, 11/16/05 00:07:26 EST

Specialists?

Thomas mentioned a few of the skills going into a fancy blade and hilt, there are others.

Engravers are almost always specialists.

A few craftsfolk do their own but really first class engraving is an art and is often the most costly part of a presentation piece.

Plating is another specialty.

If a blade is to be gold, silver or chrome plated it is sent to a plater.

Same holds true for blueing and blacking.

Metal finishing has long been a specialty especialy where strong chemicals and odd shaped heated tanks are required.

Thomas also mentioned jewels. Do you cut your own diamonds, saphires, rubies, crystals of any kind?

This is always a specialty and those mounting them are also often specialists.

Tanning the leather for a leather grip or scabard is another specialty. Yes, you could do this yourself but you do not.

Drawing wire for wire wrapped grips is yet another specialty.

Small shops such as jewelery shops DO draw their own wire in precious metals, but only when they need a special size or specific alloy.

Doing it ALL yourself would mean mining the ores, digging the gems, obtaining the fuel,

smelting the iron, copper, tin, gold and silver (each specialties),

cutting and polishing the gems,

making the steel from the iron,

forging it to suitable bar sizes,

alloying and casting the brass or bronze,

drawing the wire,

cutting the tree, seasoning the wood,

forging the sword,

grinding the sword,

heat treating the sword,

polishing the sword,

making the furniture,

fitting the grip,

Mankind has been a cooperative society for hundreds of thousands of years.

The earliest known history of man is evidence of trade and specialties, mining, loging, smelting metals.

Artists and craftsfolk have taken advantage of others specialties for a very long time.

The weaver has traded with the spinner and the smith with the smelter.

Each doing a job more efficiently and better than the other. Making a sword was this way with many specialists involved.

Cheap labor did the work of modern machines.

Today's blade smiths probably do more in house than the bladesmith of just a few hundred years ago.

Machinery and modern cutting materials has replaced much of the drudgery work that was subbed out in earlier times and some of the specialists may not be available.

SO, How long does it take to make a sword?

It depends on how much of the job you include.

From digging the iron ore form the ground to the user's hand there are MANY stages and each has delays.

It could take a year or more.

To simply forge and grind a simple blade using purchased materials and modern equipment could be done in a day by an expert.

In fact a good hand at the power hammer can produce near net finished forged blades by the dozen a day.

Custom blades often take from a few days to a month or more to complete not including advanced pattern welding.

- guru

Alternative Titles

- Swordmaking for Dummies (Original Title)

- Sword Making Made Simple (Paw-Paw's suggestion)

- Sword Making from Chicken Salad (ptree's comment)

- SO, You want to make a sword? (Thomas's suggestion)

- Pepsi Generation Sword Making

- Hitchhikers Guide to Swordmaking

- The Lost Generation Swordmaking

- POOF! You're a Swordsmith!

|