A BLACKSMITH OF 1776

orWhat Kind of Forge was used in the American Revolution.

Historical Fiction by Jock Dempsey - © 1997

Originally published in the Blacksmith Gazette, January 1998.

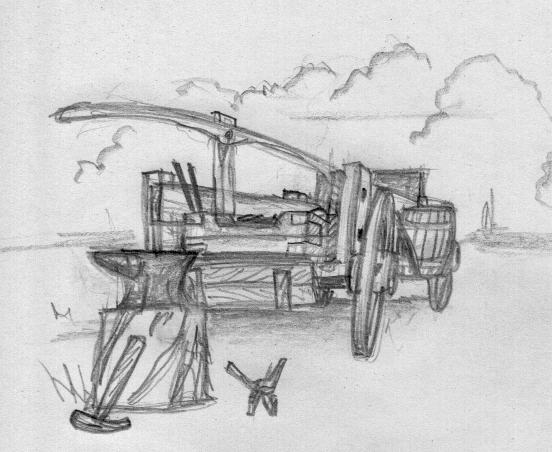

New illustration by the author

IMAGINE, you are a Journeyman smith and the war has started. You've been called to action as a smith and told to bring your tools! This aspect of going to war had not occurred to you and you are caught unprepared. You have been training with the militia for over a year. Marching and rifle practice under your Master who is also a Captain in the militia. Your Master is staying behind to produce armaments while you are now the regimental Blacksmith.You are provided a small farm wagon and your Master donates 100 pounds of bar stock and a horse to pull the wagon. The portable steel forge is an invention of the future so you are going to have to make do on the road. You load your tools including a small well worn anvil of about 100# and the bellows you've been building for when you start your own shop. The tools are a motley collection of tongs, punches and hammers you made during your apprenticeship. On the way out of town you barter a pair of tongs for a fired clay tuyer pipe at the potter's. The cabinet maker stops you and loads you up with some oak lumber and some hickory handle blanks. Your unit is moving out and you've done a better job packing your tools than caring for yourself.

On the march it is hard to concentrate but you know you need a forge and don't have all the necessary materials. The muddy road reminds you that you should have gotten some wet clay from the potter. You ask your commander if you can stop at the next stream and get some clay. He says you'll have ten minutes and he doesn't want any stragglers! He also assigns you a helper. You are lucky and find a clay bank just to the left of the crossing. You grab as much as you can using your bare hands (what shovel?) and also toss on a pile of flat sandstone from the creek bed. You've got to move. The column is just about out of sight and your wagon is considerably heavier than it was ten minutes ago! You remind yourself that you need to look for some brick and ask around if there is a carpenter. You wish you were back in your Masters well equipped shop. This would be an easy job there. The sun is getting low and you hope they break for camp soon.

Luckily no one has needed your services during the day. The rumor is that there may be fighting tomorrow. Again circumstances make it hard to concentrate on the job at hand. You are supposed to be your unit's Blacksmith, yet you still don't have a forge. You finally remember to find that carpenter. It is pitch dark now except around the fires which make it even harder to see when you look away. The carpenter you find is just 16 years old but says he can make anything. He has brought along a few tools but says they are getting awful heavy to carry along with his pack and rifle. You offer to let him store his tools on your wagon. He volunteers to help build your forge.

You explain to him what you need, a box about 12, no 16 inches deep and two by three feet. It will need a hole in one end about two inches in diameter. All the lumber you have is two inch, much thicker than you need but it will have to do. While your new friend is working on the box you set about cold cutting some iron straps to mount your bellows with. It is hard work and not the way you'd prefer to do it. You nick your anvil and dull a cold chisel. You wonder how you are going to resharpen your chisel without a grindstone. Maybe one of those pieces of sandstone will work? This is going to be more difficult than you thought. Now you are finally thinking of all the things you didn't bring with you. The carpenter made wood pegs from one of the hickory handle blanks. He is using pegs to put the wood forge box together but you need some nails or spikes. More cold forging? No. You carry your anvil over to the nearest fire and drop it. The thud surprising those sitting there. You tell them what is on your mind and ask for some help. Two eager fellows help with the bellows. One holding them in position while the other pumps erratically. The nozzle of the bellows has been wedged between two rocks and another set over it. You rake a pile of coals in front of the blast telling your helper to pump just enough to make a nice bright glow. He finally gets the idea. The small fire is refueled from coals from wood that is still being fed to the other side of the campfire. Nails do not require much heat and soon you've made a couple dozen while kneeling at the anvil and fire. You wonder how many times and in how many places other smiths have had to resort to forging at a campfire? The cold and stiffness in your knees tells you its time to quit.

The next day the rumors of battle are even worse and the previous excitement has turned to quiet tension. Your carpenter is still at work in the back of the wagon while you lead the horse and wagon on foot. With every bump in the road both you and he realize that the forge you are building is going to need to be securely anchored. You and your wagon are ordered to pull aside with the supply wagons and your carpenter back to his unit. He has finished and a neat job at that. As you pick up your rifle and prepare to leave with him but a passing Colonel tells you to stay and finish your forge. "It will be needed soon". You are shocked, you came to fight for freedom! Then you remember that you were not brought to fight but to be sure others could.

Soon rifle shot can be heard in the distance and then cannon. You are forced to finish your forge with the supplies on hand. You borrow a shovel and half fill the forge box with loose clay dirt from the side of the road. You position the clay pipe tuyer and make a surface of clay over the dirt to help hold the bowl shape in front of the tweer. Now you remember that you will need a water barrel too! Some rocks are placed around the edges of the forge box and a large flat one at the back to protect the bellows from the heat. You wished you had been able to find some bricks, this water saturated creek stone may not hold up. Worse it may spall and shatter from the heat but its a chance you will have to take.

The battle rages and you can hear the battle cries and screams of the wounded in the distance. Commanders on horses race up and down the line of wagons yelling orders to evacuate the wounded. Meanwhile, you use the spikes you made last night to anchor the forge to the wagon floor. The rough cut bars are used to support your bellows and more spikes are used. There is not enough room in the small wagon to square the bellows with the forge. The nozzle of your bellows fits but leaks too much air. Clay is used to make a seal and dirt and stones are piled around to hold it in place. Now you build a small wood fire in the freshly lined forge. Hopefully the clay will dry in time to take forging heat.

Then comes the retreat! Retreat? Why? Don't ask questions, just move. All is chaos. You throw your tools back into the wagon and start moving without putting out the remaining fire in your forge. That night there is no revelry in camp. Many are injured. You are set to work repairing cannon carriage and wagon parts. Rewelding broken chain, straighten bent parts. There is no time to do anything right. Just fix it good enough to be ready to move. When, no body knows. Soon maybe. The list of things to repair grows and grows. Finally an officer is put in charge of priorities and you are given a helper. You work through the night. Occasionally the wood sides of your forge start to smolder and water is applied with a hiss. Your feet are wet. You find yourself working in a mud hole of your own creation. Sometime before dawn you are told to pack up. Unfinished work would have to wait or be left behind. You rapidly pack up, tossing anvil and tools in the back of the blackened wagon. The fire is quenched, something you know better than to do lest it damage the forge. All is done in haste. You do not remember the passage of time.

Soon you are on the road. Traveling to another battle? It is then that you remember you haven't slept for two nights and can't remember when you last ate. You sleep sitting up in the wagon, the horse doing the driving. Occasionally you wake with a start from the pain in your neck from sleeping upright. That night when camp is made you remember to eat before starting work. You inspect the rough clay lining of your forge. It is cracked and loose. You smear some mud in the cracks and on the exposed wood. You start a forge fire without waiting for the mud to dry. It hisses and steams. All the time you are in the field, the forge, a box of dirt and clay, will be patched, rearranged and a stone or two replaced, but no more. It will never be "made right".

While getting up a heat you survey your tools. You lost a pritchel, a drift and a pair of small tongs while packing in the dark and mud of the previous morning. You curse and tell yourself to be more careful. What else is missing? You ask about your carpenter friend. No one knows, they'll ask around. While you are working the news comes. The carpenter didn't make it. He was one of the first casualties. You notice his leather tool roll in the corner of the wagon. You choke back a rising swell of emotion. You had only known this boy, no, man for one night. The two of you had barely talked. Yet he seemed like a brother. How could that be? Later you would open his tool roll and find tools obviously made by talented caring hands. The polished hard wood parts of each tool delicately decorated. Carved just deep enough to be seen yet not so deep as to affect their use or make them rough to hold. Each marked with the makers initials. All you had known him by was Jake for Jacob. Never asking his last name. You carefully replace the tools and stow them in the wagon.

Days, weeks pass. How long has it been? Every day the same, what day is it, no one knows. Pack, move, advance, retreat, the work of one day the same as the next. You are cold, tired, dirty and hungry. Many are sick with "camp fever" and will die. You are not wounded but lack of sleep and bad food has taken its toll. You fire your forge with wood. The wagon mounted forge warms your face but the rest never warms. You find yourself hunching over your work try to warm yourself. Your back and shoulders become stiff from this bad working posture. To work becomes torture.

Then one bright morning an officer introduces you to a young man that he says is a Blacksmith. He is fresh and sharp of eye. You shake hands. He has the grip and calluses of a smith. The officer says you can go home now! You mumble something about these being your tools. The young man says he'll take good care of them. The officer doesn't understand, but says you can take the horse you came with, the NEW man has his own. You are too tired to respond. You pack your bed roll and your unused rifle. While tieing them to the horse you remember one last thing. The carpenter's roll of tools! You add them to your traps, say good by to no one in particular and leave. You never see the wagon, forge or your Journeyman tools again. On the way home you think of the compactness of the carpenters tool bundle compared to the wagon load of tools you had just left behind. You say to yourself, "My, wouldn't it be fine to be a carpenter!"