| |

|

|

|

|

-GURU

|

|

Tonights demo is by Bruce Blackistone our resident historian and expert on medieval things is a full time

Marklander Viking

and master of the Longship Fyrdraca. He works for the National Park Service.

|

|

ATLI

|

|

"The multiplicity of methods of skinning a cat is of little comfort to the feline involved."

Uncle Atliís Very Thin Book of Wisdom

|

|

Atli

|

|

Alternative Methods of Making Spearheads.

Continued from Spearheads Part I

I've spent most of my time trying to duplicate medieval techniques for forging spearheads. Over the years I've come across a number of cheap-and-dirty methods using modern materials or techniques. The simplest method, of course, would be to just make the head and socket separately and tack it all together with a buzz-box. The following methods are a little more off the wall than that, but are easier for many people than the 18 step method illustrated in part I.

|

|

Atli

|

|

Tanged Spearheads

|

|

|

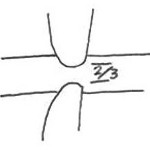

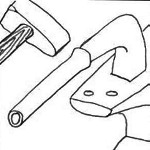

Figure T-1

Click for Detail |

Using 3/8" (9.5 mm) or 1/2" (12.7 mm) bar, fuller to about 2/3 the width of the bar and about one or two inches (25.4-50.8 mm) from what will become the blunt pointy end. (For the sake of clarity the business end of the spearhead is noted as the "sharp pointy end", and the tang end is the "blunt pointy end". This is a transference from the longship where the bow is known as the "pointy end", and the stern is known as the "other pointy end".) Fullers with a slight offset towards the sharp end are good, and spring fullers will suffice. You do not want a sharp corner, due to the propagation of stress cracks.

|

|

|

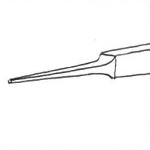

Figure T-2

Click for Detail |

Keeping the shoulder area off the anvil, forge the tang out into a long, even taper about two to four inches ( ~50 - 100 mm) long.

Keep the sides even and square.

Forge out the sharp pointy end for the spearhead as per part I and harden and temper.

|

|

|

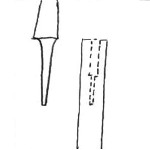

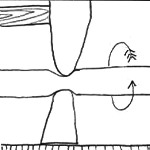

Figure T-3

Click for Detail |

Select an appropriate shaft, ash being preferred. I usually drill tang holes in two stages, the deeper one just a little narrower and a touch shallower than the end of the tang, and then using the first drilling as a pilot hole, a slightly wider one to accommodate the thicker upper part of the tang.

|

|

|

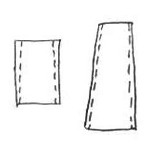

Figure T-4

Click for Detail |

Wrap the spearhead in wet rags and heat the tang to a black heat. Wearing heavy leather gloves to protect from ejected hot gasses and steam, insert the tang into the shaft. This may take a couple of heats to get it all the way in. Do not overheat the tang to a red. Too hot results in excessive charring and a loose fit. It's also a good idea to wrap some layers of sturdy cardboard or cloth around the blade and point if it's at all sharp to protect your hands from a slip-cut.

|

|

|

Figure T-5

Click for Detail |

Ferrules are frequently used to reinforce the spear shaft and to keep the head from splitting out. The two types that I've used have been straight ferrules tapered on the inside, and conic ferrules. The later are frequently found on garden implements, which commonly use tang connections to their wooden handles. Unless your blade is narrower than the shaft, you should put the ferrule loosely over the shaft before burning-in the tang.

|

|

|

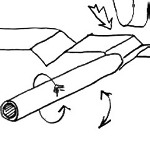

Figure M-1

Click for Detail |

The Markland Method

This method was shown to my by Fred Scholpp (Durgil Everseeker), who has served as armorer at Jamestown for a number of years.

Select a piece of Schedule 40 or other thick-walled steel pipe, heat to a good yellow and start to flare it on the socket bick. Most of the work is accomplished by using a light to medium weight straight peen as the pipe is rotated.

Hammering the pipe onto the bick end-on is of limited usefulness, and frequently results in the pipe stuck on the bick. The amount of taper achieved is a matter of patience and personal choice.

|

|

Atli

|

|

SPECIAL NOTE: When cooling pipe in the slack tub, be sure to point the "cool" end away from your face and body. The hot shower of scalding water and steam that sometimes erupts from doused pipes will do nothing to enhance your day.

|

|

|

Figure M-2

Click for Detail |

Using fullers or a bottom fuller and similar peen on your hammer, fuller down the pipe to create the neck of the spearhead, rotating as you go. The pipe does not need to be completely closed, depending upon the proportions that you're looking for.

|

|

|

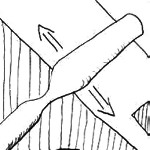

Figure M-3

Click for Detail |

Cut the pipe so that the unit is about eight to ten inches (~20 - 25 cm) long.

(Remember, very long blades put a lot of stress on the neck if they're thrown.) Bring the blade end up to a bright red, lay it on the anvil and start to flatten from the back to the front. Avoid overheating and scaling, since you're going to have to weld it.

When you have the inside cavity down to about 1/4" (6.35 mm) or a touch less, sprinkle borax down the pipe with a spoon, bring it up to a welding heat and weld it up 2 to 3" (~6 - 8 cm) at a time from back to front. Once the pointy end is welded up, you can start forging it into a proper spear blade, grind, harden, temper and sharpen. Most of the pipe I've dealt with has been low to medium carbon steel, so quenching and tempering should take that into account. On the other claw, tough is better than sharp if it's a throwing spear.

|

|

|

Figure M-4

Click for Detail |

The spear blade profile is somewhat restricted by the size/volume of metal in the pipe, but it should prove sufficient for anything that is not too outlandish.

|

|

|

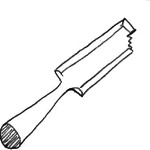

Figure A-1

Click for Detail |

Atli's Method

This method was precipitated by two of our crew, Terry L. Neill (Anarra Karlsdottir) and Janet D'Agostino-Toney (Ana Ilevna), who donated a broken chisel to me, knowing the transformative powers of blacksmiths.

Haunt yard sales, flea markets, tailgate areas and other likely venues, thinking of "the transformative power".

|

|

|

Figure A-2

Click for Detail |

A broken, socketed woodworkers chisel is ideal for transformation. (Please note- converting a new or perfectly good chisel from a useful tool into a weapon is just plain wrong. Find one that has been abused or otherwise messed up.)

|

|

|

Figure A-3

Click for Detail |

Forge out the chisel into a spear blade. Since this is high carbon steel, do not overheat (no more than bright red or lowest of oranges) and be willing to take your time about it. Forge thick and grind thin to eliminate any decarburization. (Or you can leave it "cased" in the decarburized steel for extra toughness, just grinding down the edges.)

|

|

|

Figure A-4

Click for Detail |

Heat to critical temper and quench in oil dipping the pointy end up and down to the socket. Do not quench the socket. Temper to blue. Remember, you want tough rather than hard.

|

|

|

Figure F-1

Click for Detail |

End Ferrules (Butt Spikes)

These were fairly common on spears from the classical era to the 19th century, and their positions in grave finds are one of the methods by which we know how long some spears actually were. The best things about them is it gives you a safe way to park your spear when there's nothing secure to lean it against, and it might keep some modern barbarian from stuffing your carefully crafted spearhead into the dirt.

|

|

Atli

|

|

Take a piece of appropriate diameter thick walled pipe. On a swage block, deep anvil step, or other appropriate angled surface start drawing the end down with the peen of the hammer, rotating and rocking a bit as you go. Start drawing the end out as spike as you go. While you can still see a touch of light through the end, sprinkle some borax down the pipe, tapping it down so that if gets to the end. Bring to a welding heat and forge weld it closed on the anvil.

|

|

|

Figure F-2

Click for Detail |

Draw the spike out until it's no less than ľ" (6.35 mm) at the end. There are two reasons not to make the spike on the end ferrule too sharp: It's a BAD idea to have any weapon as dangerous on your end as on the business end, and this is the end that goes in the dirt all of the time. A thinner end, upon meeting a rock, could bend or "J-hook" and get ugly. Drill a cross-hole (straight through with the spear shaft in place, if possible) and rivet to the shaft. As opposed to the cross pins illustrated in Spearheads I, these should be closed down tight to the ferrule to keep from snagging on anything or anyone.

|

|

Atli

|

|

Commentary on Weaponry:

I'm sure there are as many methods of doing this as there are blacksmiths out there, but these have proved workable for me and a number of folks in the Markland Confederation. The laws of Charlemagne (or Big Charlie, as we know him) state that "a man's arms are a spear and a shield". The wise sayings of Othinn, the Havamal, give the Viking view:

Far from his arms in the open field

A man should fare not a foot.

One never knows on a distant road

When one may have need of a spear.

As a weapon a spear is much underrated, having neither the glamour of the sword or the utility of the axe, but in reality they were fast and deadly. It is no different today, and even an aluminum wall-hanger can be dangerous. To bear arms is both a privilege and responsibility. A spear is no different, so be careful in how it's carried, stored and displayed.

As far as modern blacksmiths and weaponsmiths are concerned well-forged spears should be popular with any medieval reenactors. Their use in battle reenactments is a little problematical, (although in England they use unsharpened spears with ball bearings welded to the points) but they look good in the camp, and provide an entry-level weapon for new members and an expansion of options for more experienced members of medieval reenactment groups, Scadians and Rennies.

|

|

|

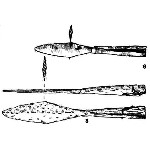

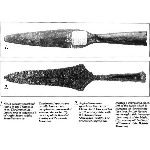

Figure 20

Click for Detail |

Two examples of Anglo-Saxon Spearheads with cross sections.

Notice that the sockets are not complete or fully welded.

|

|

|

Figure 21

Click for Detail |

1. Top, Ninth Century spearhead found in the Thames

2. Anglo-Saxon spearhead, 6th or 7th Century with "strikened" cross section.

|

|

|

Figure 23

Click for Detail |

Tenth to eleventh century warrior.

|

|

Atli

|

|

Any Questions?

|

|

JimG

|

|

You said from the position of the buttcaps they determined some lenghts? what was the lenght?

|

|

dunchadh

|

|

I am a scadian and I forge up bodkin points for arrows,

I have had an ongoing problem with getting the socket to fit correctly and be straight with the shaft.

Any suggestions?

|

|

vicopper

|

|

Nice demo Atli! Thanks. Very clear and good ideas I'll use on some other items.

|

|

Brogan

|

|

Can black pipe be used for spears?

|

|

GURU

|

|

Nice demo Bruce.

|

|

Atli

|

|

Most early medieval spears were about 6' long. Seldom under 5', and seldom more than 8'.

|

|

Atli

|

|

Lining up sockets and blades: You've mostly got to eyeball it, sighting down like you'd sight down an arro shaft. Any souce of localized heat at the transition would help.

|

|

Atli

|

|

I like the fact that techniques for any one project are transferable to all sorts of other items.

|

|

JimG

|

|

great demo alti

|

|

Atli

|

|

Black pipe is very good for the butt ferrules, and will suffice for spearheads. The ones I've done using it seem to hold up fine, but aren't exactly "royal" grade. Good enough fro a fee man to bear, however.

|

|

dunchadh

|

|

good demo very usufull maybe i will use it for one of our local A&S meetings

|

|

Brogan

|

|

Cool.... Thanks for the demo!

|

|

Atli

|

|

Thank you. It just took a few years to pull it together. I ran across an arrowhead demo at another site where the techniques were nearly the same, so I guess we're on the right track. Tonight's demo is sort of a "get them on the field" without hopping through the hoops of "authenticity".

|

|

Atli

|

|

If you're doing a demo, don't forget to include "Part I" posted earlier in the iForge.

|

|

Atli

|

|

Jock will also be posting some pictures and illustrations from contemporary sources for this at a later date. I might add one or two others. At least the attributions will get you started for research purposes.

|

|

Atli

|

|

Aye; if there are no more questions, I guess we'll wrap up this session. Thanks for looking in, and thank you Jock.

|

|